For seven years, Yeweinishet “Weini” Mesfin lived out of her Honda Civic.

A night janitor at Disneyland Resort in Anaheim, Mesfin decided not to tell family and coworkers that she was homeless, outside of one or two people.

When she died, barely a week after her birthday, she was alone in that same car — a 61-year-old woman, worn out, suffering from heart problems. A victim of her own secrecy, nobody in her life could be there to help her.

Relatives and friends began a frantic search when she failed to show up at work on Nov. 29, 2016, or get in contact. Because they had no clue where to look, it took 20 days to discover Mesfin, dressed in exercise clothes and clutching her keys, in the driver’s seat of her dark green 1999 sedan parked at the gym where she showered.

Her decomposing body remained undetected until a strong odor alerted a security guard.

Now, more than a year after her death, Mesfin’s private struggle is the subject of public debate.

“They are not even allowing her to rest in peace after her passing.”

A recent union-commissioned survey of 5,000 Disney employees — one-sixth of the resort’s workforce — led to headlines about the wages of workers who say they don’t make enough to pay for food, housing and medical care. Mesfin soon emerged as the subject of social media posts and stories tying the way she died to her own paycheck.

But her story is more complicated — her life as an immigrant from east Africa richer and her financial struggles deeper than that of the wage-gap poster child she has become, say relatives and friends.

While recognizing legitimate concerns over a livable wage, they fret that Mesfin is being exploited.

“They are trying to use her situation to push forward their own agenda,” said her nephew, Jerome Isayas, a computer network engineer in Virginia who filed the missing person’s report on his aunt. “I support the idea that Disney needs to pay its workers more in this day and age, but not at the expense of someone who was a very private person.

“It’s very sad. They are not even allowing her to rest in peace after her passing.”

Privacy — and pride — had prevented Mesfin from asking for help. She even turned down assistance from a homeless advocate and swore to secrecy one close friend who had figured out Mesfin had no place to stay.

What may never be fully understood: Why did she live that way for so long? Why didn’t she let someone help her?

If strangers are going to contemplate what happened to his aunt, Isayas wants them to at least know more about who she was before she became homeless. Her friends, including those who call for higher wages at Disney, hope that talking about Mesfin will open people’s eyes to what might be happening to someone they see every day.

Vanessa Muñoz Diaz worked for three years with Mesfin cleaning restrooms in the Cars Land area of Disney California Adventure theme park. She moved to Illinois last year to find a better paying job, but the friend whose name she lovingly likened to Winnie the Pooh stays on her mind.

She said a few days ago: “I saw a car the other day covered in snow and went to clean the passenger side just to see if anyone was in there.

“That’s how paranoid I am that somebody might die in their car.”

From Eritrea to Anaheim

The autopsy report from the Orange County coroner attributes Mesfin’s death to an enlarged heart. No foul play.

Thousands of homeless people around Southern California live in motor vehicles — cars, trucks, vans and aging RVs. Often the only acknowledgment of homeless people who die in their cars is a line on a coroner’s spreadsheet.

But sometimes such deaths do make the news, as with the family of four — a man, a woman and two young children — who were found inside their van March 15 at a Garden Grove shopping center parking lot. It is believed they died accidentally from carbon monoxide poisoning.

Mesfin was among 203 people whose residence the coroner’s office listed as “no fixed abode” when they died in 2016, the deadliest year on record for homeless people in Orange County. At least 15 of them died in parked vehicles.

There were no news reports when Mesfin’s body was found around noon on Dec. 19, 2016. None described the celebration of life held in a local church the morning after New Year’s Day 2017, or when relatives buried her in the Washington, D.C., area, where many of them live.

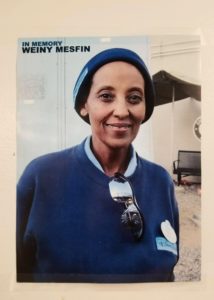

A memorial card handed out at the gathering for Mesfin includes a photograph of her from better days. Her thick dark hair is loose from the work beanie she always wore on the job, her large brown eyes focused on something off camera that makes her smile. Her face is full, her lips shine with red lipstick, and thick gold hoops dangle from her ears.

The woman in that photograph is the Mesfin that Jerome Isayas remembers best — not the one in a somber image posted on Facebook where his aunt’s face is thin and drawn, with dark circles under her eyes.

Mesfin was born to a well-to-do Eritrean family and grew up comfortably in what was then part of Ethiopia. Her father held a high-level government post while her mother stayed home to raise their two boys and two girls. Mesfin was privately educated and spoke several languages including fluent Italian, a legacy of her country’s history as an Italian colony.

Isayas describes his aunt — whose first name is pronounced “Yuh-way-ni-shet” and her nickname “Way-knee” — as a gentle spirit with a strong backbone and good sense of humor. She loved to dance to ’70s soul and disco music broadcast from a nearby American military base. She entertained friends by cooking Italian food.

Get top headlines in your inbox every afternoon. Get the free PM Report newsletter.

Mesfin came to the United States in 1982 to join her then-boyfriend, settling with him in a shared townhome in Pomona, Isayas says. Mesfin, who had some college and a decent job at a bank, appeared to be doing well.

But she split with the boyfriend after about 10 years, her nephew says. Not much later, her mother was murdered back in their homeland.

The family never learned if the 1993 murder — a brutal mutilation at the Mesfin home in Eritrea’s capital city of Asmara — was politically motivated, but many of them left for the United States. A few settled in Los Angeles, most in Maryland and Virginia. Mesfin’s father, who died at age 95 in 2014, remained in his native country.

Relatives could never convince Mesfin to leave the warm Southern California weather and join them on the East Coast, but she would visit for weddings and holidays. She kept an apartment on Lemon Street in Anaheim for nearly 10 years. Then she rented rooms from others.

Her final address was a P.O. box.

“When she took the job at Disney, it was just until she got something better.”

Isayas has no idea when his aunt started living in her car. He didn’t learn about that until her death. Though he last saw her on a visit to Southern California around 2005, she often called or texted family back East, including on Thanksgiving Day 2016 — the week before she went missing.

The family knew she had scrambled for work after losing her bank job and that she had medical expenses. She kept telling them her job with Disney — cleaning toilets and picking up trash — would be temporary. What she didn’t reveal was the extent of her debt.

Had he realized how tough life had gotten for his aunt, Isayas said he would have tried harder to convince her to move to the D.C. area, close to relatives willing to help.

“When she took the job at Disney, it was just until she got something better,” Isayas said.

Disney years

Employment records show Mesfin began working part-time at the Anaheim theme park in 2007, said Suzi Brown, the vice president of communications for Disneyland Resort. Mesfin became a full-time “cast member” (Disney’s designation for employees) in 2009.

“I didn’t know her personally, but I know she was beloved by coworkers,” Brown said.

Mesfin was third-shift custodial, with typical hours starting at 11 or 11:30 p.m. and ending around 8 a.m., according to coworkers. They figure her pay at the time of her death was around $13 or $14 an hour. Brown would not disclose Mesfin’s wages, citing confidentiality.

Mesfin ended up training other employees. A meticulous taskmaster, she believed that any job, including wiping away a urine line from the front of a toilet bowl, needed to be done well. Soft-voiced and exactly 5 feet, 2 inches tall with a bad knee that made her limp, Mesfin commanded respect for her attention to detail and the swiftness with which she carried out her work duties.

“She’d be done with one restroom and I’d still be in the middle of one restroom,” said Diaz, who is not half Mesfin’s age. “That lady, she moved fast.”

Mesfin wore a fanny pack around her waist to store the ink pens she liked to collect, tissues, ibuprofen, bandages and a little knife she used to cut the fruit that seemed to be the only thing she ate. Firm but kind, she addressed coworkers with the endearment “darling,” mentoring them on life issues as well as cleaning tasks. Diaz recalled: “She wanted me to not hold grudges and get along with everybody.”

But Mesfin suffered from heart problems apparently caused by a virus. Emergency room visits generated medical bills. The stress, on top of how hard she worked and the fitful sleep she likely got in her car, caught up with her.

The week before she went missing, Mesfin had told Diaz she wasn’t feeling well because of her blood pressure and an inability to relieve herself.

“When you saw her at work, she always looked so tired,” Diaz recalled. “At the last break, she would go to the cafeteria and immediately put her head down and knock out for 15 minutes. I’d sit at the table next to her and watch her. I’d have to wake her up.”

But Mesfin never complained, Diaz added: “She’d just get up and go back to work. She was never sitting down. Never. Unless it was to take her break.”

When her supervisor would ask if anyone wanted to do an extra shift, Mesfin, who had seniority, always did.

“She would work six days whenever that was offered,” said Heather Rodriguez, who worked occasionally with Mesfin over a two-year period up until 2015. “She never called in sick as far as I know.”

Rodriguez, 28, recalled spotting her old colleague at a Del Taco one summer day in 2016 and being alarmed by the unkempt appearance of the baggy sweatshirt and cargo pants Mesfin wore. But Rodriguez didn’t approach Mesfin, thinking she would not be remembered.

That missed opportunity makes Rodriguez cry with regret.

“I should have gone up to her and said something,” she said in a shaking voice. “Maybe I would have got some information from her.”

Debt and determination

Mindy Martin, another coworker who became a close friend, did coax the truth from Mesfin.

In the six years that Martin worked with Mesfin, Mesfin never invited any coworkers to visit where she lived. If asked about her home life, she would only mention a mysterious roommate.

But in early 2016, Mesfin asked Martin if she could have her mail sent to Martin’s home, saying she didn’t want her roommate to see her correspondence. That made Martin suspicious. So did the constant mail Mesfin got: envelopes with the words “Final Notice” and “Please Respond Immediately” stamped on them.

Under Martin’s questioning, Mesfin finally revealed she had lived out of her car for at least six years, kept her belongings in three rented storage units, and cleaned herself at a 24 Hour Fitness gym, whose location she did not disclose. Mesfin said she was determined to pay off her bills — credit card payments and payday loans — before seeking a place to stay.

Martin never dared ask how deep she was in debt.

“As hard as it was, I just had to leave it alone.”

Martin said Mesfin also wired hundreds of dollars every other week or so to people she said were relatives, but Isayas said he had no knowledge of that.

“She had money going everywhere except to herself,” Martin said.

Occasionally, Mesfin booked a motel room so she could sleep better. She turned down an offer to stay at Martin’s home because she was afraid of dogs, telling Martin she had been attacked once.

Martin suggested calling a homeless shelter, but Mesfin countered that there were no shelters where she could sleep during the day and leave for work at night. If Martin tried to give Mesfin money, she’d return it unspent.

“As hard as it was,” Martin said of her frustrating attempts to help her friend, “I just had to leave it alone.”

Paul Leon at the Illumination Foundation, one of Orange County’s largest homeless services providers, also reached out to Mesfin. Leon said another woman he had once helped was a Disney parking lot attendant who somehow knew of Mesfin’s misfortune. She arranged for Leon to meet Mesfin near downtown Santa Ana sometime in 2016.

Mesfin told Leon, a former public health nurse, that she was OK and didn’t need any help. That’s not unusual, said Leon, because people often won’t think of themselves as homeless, especially if they are in their car, figuring they will get back on their feet. Some manage in their cars for years, he said.

Like her nephew and her friends, Leon wishes he had been more persistent with Mesfin. Even for experienced case managers, it can take multiple encounters over the course of months — sometimes years — to convince someone who has been chronically homeless to accept help, he said.

“What we always tell people is to keep saying hi, keep engaging them in conversations. Listen to them and let them know we know people who can help.”

Frantic search

Martin believes she is the last person to speak to Mesfin. Early in the day on Nov. 29, 2016, she asked Mesfin to run to the bank and deposit $25 in her own overdrawn account before noon. Mesfin did, but when Martin tried to reach her about paying back the money, got no answer.

Then Mesfin didn’t show up for work and didn’t call in. Her friends knew something was wrong.

By the second day, coworkers put out word on social media. They began calling hospitals and visiting old addresses. Martin contacted all the homeless shelters in Los Angeles, but told nobody, worried Mesfin would eventually show up and feel betrayed.

On the other side of the country, Mesfin’s family had also become alarmed after not hearing from her. Isayas filed a police report the week she went missing. Mesfin’s Los Angeles family members and coworkers posted fliers around Anaheim and canvassed the neighborhoods where she once lived.

Brown said Disney security also requested Anaheim police do a welfare check and continued making calls to different police departments. The company maintained Mesfin’s status as an employee until she was found dead, Brown added.

Regular theme park guests noticed her absence and asked where she was.

“Everybody was scrambling, trying to find her,” Isayas said.

He got the call from police about his aunt’s death a few days before Christmas. He told family, texted some of her friends. A Disney crew supervisor broke the news to her coworkers.

When Isayas flew out to Anaheim to take care of the body and personal belongings, he visited the four-level parking structure at the Orangewood Avenue gym where Mesfin was found. He walked from one level to the next in a spiral, trying to determine where she could have parked and gone unseen. That was a detail police would not share but he wanted to know.

“I’m really taken aback by the fact it took so long to find her,” he said. “It boggles my mind.”

So did learning that Mesfin was homeless, for all who thought they knew her.

“My heart dropped and I wanted to just disappear,” Diaz recently wrote on a Facebook post in which she encourages Disney CEO Bob Iger to cut his multimillion-dollar compensation and raise the pay of company workers.

But she is hard on herself, too, like others who think they failed Mesfin.

“I felt like I hadn’t done enough.”

/SCNG staff writer Scott Schwebke contributed to this report/