BY MASTEWAL TADDESE TEREFE

We kept the imperialists at bay, but it wasn’t enough

Like many African countries that were colonised by the British, Ethiopia’s educational system strongly privileges the English language. I learnt this first hand going through school in the capital Addis Ababa.

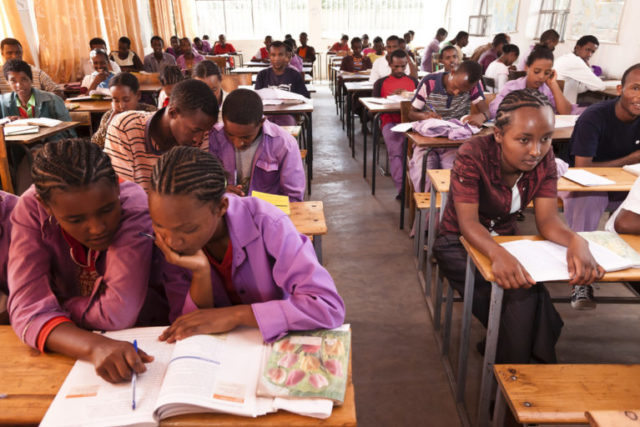

Along with my classmates across the vast country, I was taught in my local language from Grades 1 to 6 (ages 6 to 12). But after that, the language of instruction switched. History, maths, sciences and the rest were now taught in English, while Ethiopia’s official language Amharic became its own separate subject.

Growing up in Ethiopia, fluency in English was considered a mark of progress and elite status. At my school, we were not only encouraged to improve our proficiency, but made to feel our future depended on it. When I was in grade 4, one of my tasks as a class monitor was to note down names of classmates I heard speaking Amharic during English lessons or lunchtime. Our teacher would enforce a 5-cent penalty for every Amharic word that slipped through our lips during lessons.

At the same time, we were proudly educated in Western history and literature. I learnt to take pleasure in reading books in English. I listened to American songs. And I looked to emulate the lives of the people I saw in Hollywood films.

At primary and secondary school, we were taught about Ethiopian history too. But many aspects of the country – from its philosophy to its architecture to its unique methods of mathematics and time-keeping – were neglected. I left school feeling I lacked a coherent understanding of my country’s history. And today, like most of my classmates, I would struggle to write even a short essay in Amharic.

My experience no doubts resonates with many people across Africa, where colonialism elevated European languages and history in the education system while devaluing local languages, methods of instruction, and histories. This is what has spurred vigorous movements across the continent today calling for the academy to be decolonised.

The strange thing though is that Ethiopia was never colonised in the first place.

Native colonialism

So how did the country’s school system come to be the way it is? According to Yirga Gelaw Woldeyes’ brilliant new book, Native Colonialism: Education and the Economy of Violence Against Traditions in Ethiopia, the answer is that Ethiopia was “self-colonised” and that education played a big part.

In the academic’s extensive study, he sets out to show “how and at what cost western knowledge became hegemonic in Ethiopia”. He suggests that the 1868 British expedition to Abyssinia, which resulted in the British looting massive national treasures and intellectual resources that Emperor Tewodros II had accumulated over time, was a turning point in Ethiopians’ perception of power. Although the Emperor’s defeat in Magdala did not result in the country’s colonisation, it brought about a new, outward-looking consciousness. “This reaction to the European gaze created the desire to acquire European weapons in order to defend the country from Europe,” writes Woldeyes.

Successive rulers maintained a contradictory relationship with Europe – between friendship and enmity – until Emperor Haile Selassie, who ruled up to 1974, initiated a period of radical westernisation post-WW2. In that process, Woldeyes explains, Haile Selassie entrusted certain elites to establish Ethiopia’s modern education system. This group was educated in Western languages and teachings. They embraced European epistemology as a singular, objective basis of knowledge, seeing it as synonymous with “modernity” and naturally superior to the local.

These elites, who Woldeyes refers to as “native colonisers”, introduced a system of education into Ethiopia that mimicked Western educational institutions. Contributions from traditional Ethiopian educators such as elders, religious leaders, and customary experts were squeezed out.

The result is that Ethiopia’s schools came to lack a meaningful connection with the culture and traditions of the communities in which they are located. Instead, they prepare students in the skill of imitation using copied curricula and foreign languages. Schooling today, argues Woldeyes, is as much a process of unlearning local tradition as it is about learning the art of foreign imitation.

This disconnect at the heart of Ethiopian teaching has many negative ramifications. An education that doesn’t speak to students’ lived experience limits their capacity to create, innovate, and deliver solutions to problems in their surrounding world. It leads young Ethiopians to feel alienated from their own culture, lowers self-esteem, and leads to a disoriented sense of identity.

Moreover, without a comprehensive understanding of their country’s history and politics, graduates lack the knowledge and skills to confront the nation’s ongoing problems.

Text kills, meaning heals

In Native Colonialism, Woldeyes does not stop at diagnosing the problem. He goes on to propose remedies – namely that the education system be reconstituted on the foundations of Ethiopia’s “rich legacy of traditional philosophy and wisdom”.

He argues that: “before the rise of western knowledge as the source of scientific truth, one’s political and social status in Ethiopia was justified on the basis of traditional beliefs and practices”. In the tradition of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church, he says, education was not a means to an end, but part of “an endless journey” of knowledge-seeking. This quest was grounded in the two core values of wisdom and humility.

Woldeyes argues that we need to put these core values back at the centre of the country’s education, which should reflect indigenous beliefs, knowledges and philosophies. This does not mean foreign ideas should be rejected. Students should be exposed to a variety of teachings. But they should, he says, be disseminated through an Ethiopian frame of reference.

Woldeyes argues that this approach was the norm in Ethiopian education for centuries. Through trade and diplomatic relations, scholarship from as far as Asia and Europe has been making its way to Ethiopia for hundreds of years. But traditionally, scholars did not simply translate these works into local languages.

Instead, they used an Ethiopian interpretative paradigm called Tirguamme “to evaluate the relevance and significance of knowledge”. Woldeyes defines this as “a process that searches for meaning by focusing on the multiplicity, intention, irony and beauty of a given text”. This unique process of inquiry is based on a traditional principle that literally translates as “text kills, but meaning heals”. It is apparent in different Ethiopian cultural practices such as the multi-layered poetic practice of “wax and gold”, allegorical puzzle games, the art of judicial debating, and storytelling.

Woldeyes’s methodology offers a potential framework for reforming the current education system in Ethiopia. It envisions a system of education centred on local priorities and ways of being, whilst also incorporating ideas from around the world.

Decolonising the academy

Woldeyes’s ground-breaking analysis demonstrates that despite the fact that no colonial power managed to conquer Ethiopia, the country did not escape being colonised in other ways.

Moreover, his study shows that decolonising education across Africa will require an investigation of how indigenous epistemologies were violently discarded. It will also entail a critical study of the modes of scholarship previously side-lined as “traditional”.

Woldeyes’s research suggests that the decolonisation movement cannot be confined to the four walls of elite educational institutions. It must reach out beyond to members of society that were previously closed out, such as traditional leaders, elders, and others.

Emperor Tewodros believed that Ethiopia needed European weapons to defend the country from Europe. Today, we may need native epistemologies to take back the country from native colonisation.